Zephyr's "Wild Style" title sequence #ArtInTheStreets

To fans of hip hop, "Wild Style" is the ultimate embodiment of the culture: MCing, DJing, b-boying, graffiti-spraying!

The title sequence of the film is one of the most memorable and creative of any hip hop film and the animation celluloids are on display at MOCA as part of Charlie Ahearn's room at the "Art in the Streets" exhibition.

The Art of the Title Sequence website does does what it says ;) And it brings us a great interview with the Wild Style title sequence creator, graffiti legend Zephyr (aka Zroc in the film.)

Excerpt of the interview. Read the whole shabang here.

Art of the Title: Were you involved with animation previously?

Zephyr: No. The “Wild Style” animation project was my introduction, although I used to make flip books.

ATS: How did you develop and mix the various artistic styles (the “Wild Style” morphing, “Rap,” "Break,” “Pop”)?

Z: Charlie Ahearn was a great director. He had very specific ideas about everything in the film, and was closely involved in developing the aesthetic of the art in the opening sequence. The graffiti styles used for the words “Rap”, “Break” and “Pop” were all variations of things I was doing on walls and trains at the time. There is a generic quality to my graffiti, but there is also something very distinct about my graffiti work. Maybe that sounds like a contradiction, but graffiti writers will always recognize my stuff immediately. I would say that the different lettering forms were guided by Charlie, but they are definitely “Zephyr-style”. It’s weird to be talking about this now. It seems like a million years ago…

|

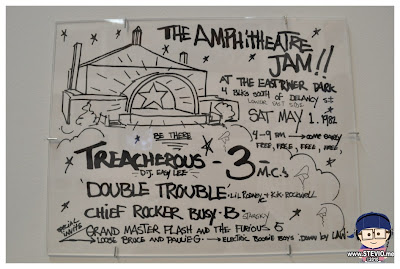

| Original "Wild Style" (amphitheater scene party) flyer 1982 |

ATS: At what point was the sequence created? The star at the end of the sequence is an interesting example of the iconography of the film.

Z: The live footage already existed, so we modeled the animation to dissolve smoothly into the live footage.

ATS: How did you mold the visuals to the music?

Z: Joey Ahlbum created a beat chart according to the soundtrack, and we worked from that.

ATS: How were you able to represent the styles of your peers and friends so well?

Z: I assume you’re referring to the train rolling by. That was easy. Copying other writers’ stuff comes pretty naturally to me, although writers will always execute their own signatures better than someone else will, of course. The train was cardboard, and it rolls by very quickly. If you saw it “frozen” you would see that I probably didn’t really do them justice. I think I did a “Bus” piece that was just plain lousy.

ATS: How did the idea of animating the graffiti come about? Are there other examples of this from this era?

Z: Charlie Ahearn had a vision. He wanted to bring “black book” drawings to life. He urged authenticity and rawness. He didn’t want it polished up. And no, this had never been done before.

ATS: What was it like collaborating with director Charlie Ahearn?

Z: It was fantastic. And I will forever be grateful to Charlie. I was a 19 year-old degenerate when Charlie approached me to work on the art for the movie. His faith in me helped me take myself a lot more seriously, as an artist and a person. I will always remember him as one of the people, early on, who recognized that I wanted to be accepted as an artist and not remain a perpetually stoned graffiti writer. Although being a perpetually stoned graffiti writer was definitely fun for a while!

ATS: How did this movie effect your life and graffiti writing career?

Z: It felt good to be working somewhere without barbed wire and cops. But I kept writing graffiti. Charlie Ahearn even came to the train yard with me twice.

ATS: How have you dealt with personal vs. commercial work, especially considering the roots and history of the medium?

Z: In the 1980’s I did a lot of commercial work. Now I refuse 99% of the offers I get, particularly the corporate ones. Graffiti has become so commercially co-opted it’s sickening. If making it that way is partly my doing, I'm embarrassed. That’s not the legacy I wanted.

ATS: What fueled the youth to bridge graffiti with the other dominant youth cultures of MCing, turntabalism and breaking? Why was the form primarily driven by the youth?

Z: Answering that properly would require about six pages. If you ever come to one of my college lectures, you may hear me discuss that subject since college kids get boners when you mention “hip-hop”. But let’s just say that the “organic/south bronx” hip-hop “elements” theory is a good story, kind of like Santa Claus.

Graffiti existed for a decade before “hip-hop” as we know it emerged. This is not the first case of art forms sweeping up and creating associations with other, pre-existing art forms. Graffiti was “anointed” the visual counterpart for rapping, breaking, etc. Most people simply accept that association, but many do not. Some graffiti artists (Blade and Pink, for example) reject the idea that graffiti is part of the hip-hop movement.

|

| Portia and Blade, MOCA 2011 |

ATS: Did the old concept of graffiti-as-vandalism die? How is the perception different today for the people and those in the employ of the people?

Z: If a real outlaw gets a paid gig, then you have an authentic thing, but the silverware will get stolen. If someone who can draw cute graffiti on paper (or via computer) gets the gig, you have a happy art director.

Labels: Art in the Streets, Art of the Title Sequence, Blade, Charlie Ahearn, Graffiti, Hip Hop, Lady Pink, MoCA, Old Skool, Wild Style, Zephyr

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home